Rating: 3 out of 5 dangerous chunks of burger (learn to chew, maybe).

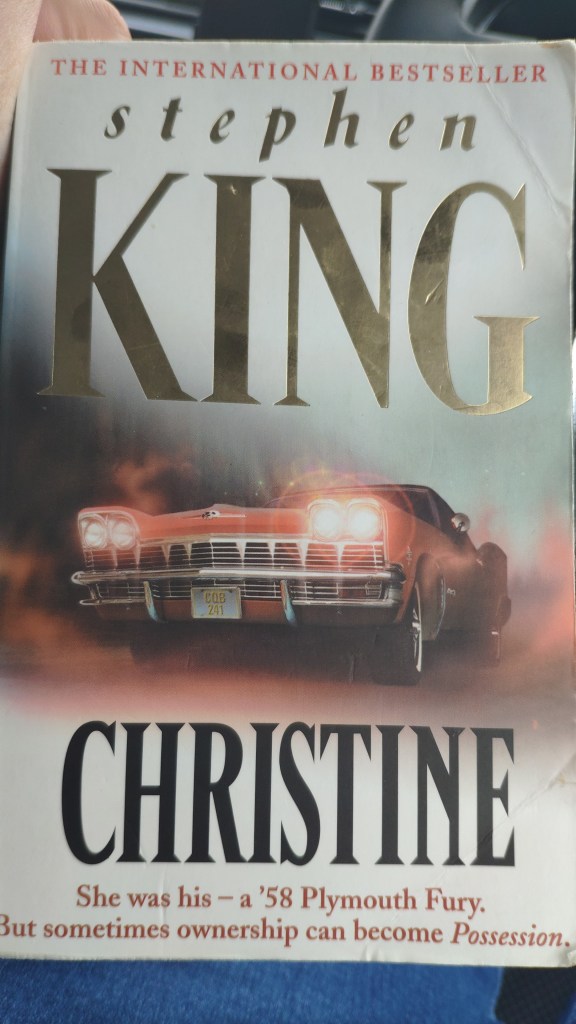

Buy Christine from Amazon here.

Buy Christine from Bookshop.org here.

Preview (i.e. no spoilers)

American teenage boys have quite a different relationship with their cars compared to the one their British counterparts have. British adolescents seem to gravitate towards small, loud numbers with shark fins and sub-woofers that woof so sub they’re practically underwater dogs. But they’re for wazzing around the estates, and occasionally venturing to McDonald’s. Whereas for Americans, whose country’s infrastructure seems entirely built around having great big roads and occasionally places to stop along those roads, it represents freedom. Freedom from parents, freedom from rules, freedom to indulge every rebel-without-a-cause dickhead fantasy they’ve had bubbling under their pubescent skins.

Christine is the culmination of this, those dreams made metal-flesh. But it’s also so much more – she represents the selfish anger of that demographic, the fuck the world mentality, the misogyny of male adolescence. It’s a really intriguing look at all of those things.

It is also, however, messy. Like teenage hormones flooding around the bloodstream of a confused idiot boy, these themes sort of float around throughout the book without ever really finding any landing strip of concrete expression or discussion.

There are some wicked-good deaths and grim decomposed corpsies though, so these at least cut through some of the more abstract theming.

Not one of King’s Rolls-Royces, but it’s far from a Morris Minor. And as you may have guessed, this analogy represents the full sum total of my car knowledge.

Review (i.e. spoilers in the mirror may be closer than they appear)

Aside from the moments when a magic car runs people over until they’re so much clumpy milkshake, I think there are two really interesting things King covers here.

The first is the American obsession (and I’m singling America out here because Christine is very much a book about US culture) with teenagers – specifically how aggrandised that period of life is. The sheer volume of books, television shows and films set in American high schools speaks to this; it feels like a time to which children aspire and adults nostalge.

This period of American life is interesting because, particularly for teenage boys, it seems to be defined more than anything as a period of rejection of anything outside of themselves. So parents become enemies, as does anything placing constraints upon them. LeBay vilifies the shitters of the world, and this exemplifies the stereotypical teenage mindset – LeBay has in many ways simply not outgrown it. So many men don’t, which is the appeal of the mileometer that runs backwards – so many men want their own personal mileometers to wheel back to a time when they felt fresh and new and like their destinies were in their own hands. Mostly because they’re whiners.

Which brings me to the second interesting thing is how this plays into misogyny. It’s a time where men start to develop fixed ideas about women, and the push-pull of ‘wanting them’ vs. ‘wanting them not to have any control over me’. And the interesting thing here is how the narrator, Dennis, himself exemplifies this, through his own sexist brain-nonsense, as well as seeing it from Arnie and the men in the book who never quite got out of the teenage mindset. Early on, he makes it clear that for these men, when they swear at their cars, they swear “female”. Christine herself is painted female – not because she is (she is a car, after all. Many things can be female but a glorified Meccano set isn’t one of them) but because that’s what LeBay, and consequently Arnie, want it to be. It feels like King has a lot to say about how men indulge their dual lusts of automobiles and misogyny at around the same age, and many never develop beyond it – but that exploration is always beneath the surface and can be hard to clarify, like trying to make a consommé out of primordial soup.

The other thing that is muddy – crude oil rather than refined petrol, if you’ll indulge the thematically-relevant, if tedious, metaphor – is what the evil actually is. There are points where it’s clear that whatever is possessing Christine is some sort of evil entity, that requires sacrifice to get started – but then there are also times where it seems LeBay started the whole shebang through the sheer force of his ever-hatin’ misanthropy. Is he a ghost haunting Arnie? Or are both he and Arnie making the ultimate sacrifices of their own lives to whatever Christine is hosting?

In a way, it doesn’t matter. Much like an idiot (me) who doesn’t understand cars (still me) doesn’t need to understand how an engine works (I don’t) to know their car is running smoothly (thank God), you don’t need to know how all the details fit together for this to be a satisfying narrative. You just get that it does work, even if you’re not sure why. That’s part of King’s genius, I think. I’m happy to be a passenger on this journey. I promise that’s the last car reference I’ll make – I’m stamping on the brakes.

One thought on “Christine (1983)”