Rating: 3 out of 5 references to ‘50s films I’ve never seen

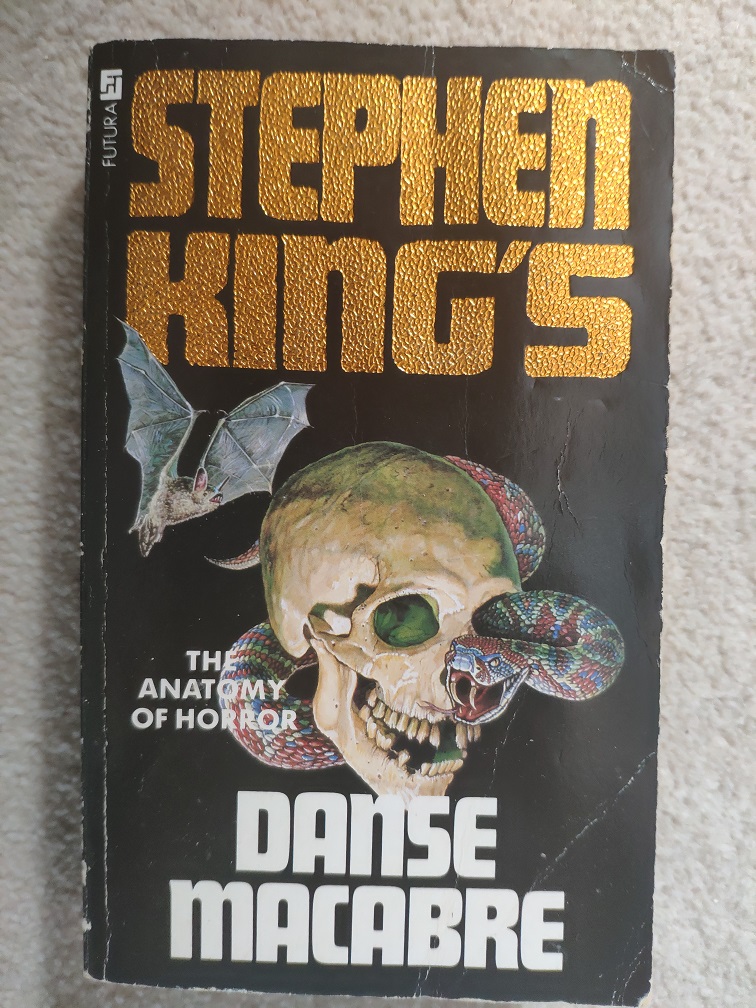

Buy Danse Macabre from Amazon here.

Buy Danse Macabre from Bookshop.org here.

Preview (i.e. no spoilers. Can you spoil a non-fiction essay?)

If you want a passionate, easy-to-follow argument that horror isn’t strictly for social aberrations like Ed Gein and Ann Widdecombe, pick this up. There are times when King tries to protest that he doesn’t want to present academic arguments and then proceeds to do so, stretching his folksy, everyday-language approach to its limits, but I don’t think that’s any bad thing. If you pick up a book that’s meant to analyse the horror genre, you can’t get your underwear of choice too knotty when the author starts to perform analysis. You can’t go into surgery but insist the surgeon doesn’t use anything sharp.

The edition of Danse Macabre I’ve read is from 1991 – but its only tweaks have been for typos since its original publication in 1981. He has released an edition in 2010 with an extra foreword entitled What’s Scary, but I’ve not been able to get hold of that legally (without buying a whole new book) and guv’nor, I’m tryin’a go straight, I swears it. So while I’m sure the newer edition references more up-to-date horror media, the one I’m reviewing focuses, for the largest lump, on films, books, radio and TV during 1950s-1970s. If you’re in the same ignorant boat as I am, you might find a lot of the references, therefore, fly over your head at such a height that you mistake them for passing birds. But even with a lack of knowledge of the reference points, I still got a lot out of the arguments King makes here – and the sheer love for the genre on display.

Review (i.e. actually talking about the points he’s making, only with much less style and understanding)

If you publicly acknowledge enjoying horror, at some point somebody is going to ask you why you’re such a goddamn piece of work. This book attempts to explain that no, I don’t actually secretly think chopping people into bits is okay but thanks for asking, in about 450 pages of careful analysis. Or maybe 350 pages of careful analysis and some autobiographical stuff that adds colour but doesn’t necessarily lend weight to the actual thesis.

King gives a couple of different shades of answers to this question. One is that it’s a means of personal catharsis, particularly for people of an imaginative bent. If imaginative people, who are capable of constructing worst-case scenarios in their heads with the expertise of professional nightmare architects, don’t have a means to channel that ability into imaginative stories, particularly those where things turn out okay… anxiety will override them like ants over a hot honey sandwich.

It’s hard to disagree that horror can be a simple exit route for emotions when everything feels too much. Global problems (e.g. climate change) and personal problems (e.g. illness, mortality, the stress of being a good parent) are often complex and unassailable, and it’s helpful to exorcise emotions through the relatively graspable, simple concept of Man With Axe. Simplicity is a very effective delivery mechanism.

His second argument is that it’s a response to societal concerns. He’s quite convincing on this. In the wake of nuclear bomb testing, we saw a rash of stories about radioactive monstrosities. When America hounded itself over a ‘red menace’, you saw stories infused with paranoia and infiltration of society by unseen dangers. And so on and on. He argues that horror is about reinforcing the norm, and its moral codes, against threats to those social rules. So yes, you see taboos enacted and morality trampled, but in the service of underlining the necessity for those things, like when you imagine a world without Terry’s Chocolate Oranges to drive home that this world is worth living in after all.

Personally I really like it when horror exercises current issues, but I don’t like it too on-the-nose. Antebellum is a good film but it’s writ too large to get too deep. The Hunt, too, is too explicit in that. Something like Get Out, or His House, is much more effective, because, as King himself says, “I like my stories without billboards”.

Finally – and while I agree with all of those points, this is the argument I find myself most aligned with – there’s the simple element of taking a good look at the things that scare or repel us. Political fears, yes, but also taboos, specifically and obviously death and its grim handmaidens. Part of the appeal of gruesome horror is that we see the internal workings of our bodies; we’re forced to face the fact that although we collectively agree to pretend that we’re more than the sum of our parts, the truth is that we can be so easily reduced to tubes and liquid, and then decay. Other taboos are explored too: sexual promiscuity, or how it would be to really dance over social lines and eat other people like they were giant walking Doritos. All of these are explored in horror, either with sensitivity or gratuitousness, and the value of the film depends on where on that line it sits.

Which isn’t to say that gross-out horror is necessarily gratuitous, or unnecessary. He makes a point of appreciating ‘junk food’ – saying that if he hears there’s an audience laughing at a horror film, he rushes out to see it. Sometimes horror done badly brings its own sort of catharsis to the table. It doesn’t mean it doesn’t have any artistic merit, although there is plenty of horror – and non-horror – that’s entirely devoid of merit whatsoever.

There’s a whole bunch of other stuff in here too – King separates modern horror villains into three distinct camps: The Vampire, The Werewolf and The Thing Without A Name. I don’t totally agree with this analysis – for example, for me zombies don’t fit into any of those categories neatly – but it’s as good a structure as any to play around with. And as you’d expect, he runs through a lorra lorra books, radio shows, TV programmes and films with very enjoyable dissections. So if any of that piques your interest, it’s definitely a good goer.

If I had to make criticisms (which I don’t, but I will, because I’m that kind of jerk), I’d say that I’d have preferred a breadth of analysis across more examples of the genre rather than delving deeply into fewer of them. It makes sense to dig into a few of them hard, but what we’re really talking about here are patterns of thought, motivation and cultural fashions, and I felt that got a bit lost. I also felt like he ruined the end of a lot of to-read books and to-watch films for me. But give the guy a break, it’s hard to present an analysis of something without going into plot details.

I’ll give him the final word in this review:

“Here is the final truth of horror movies: They do not love death, as some have suggested; they love life. They do not celebrate deformity but by dwelling on deformity, they sing of health and energy. By showing us the miseries of the damned, they help us to rediscover the smaller (but never petty) joys of our own lives. They are the barber’s leeches of the psyche, drawing not bad blood but anxiety… for a little while, anyway.”

3 thoughts on “Danse Macabre (1981)”